ABOUT

Born in 1989, Cai Ruei-Heng lives and works in Taipei. He received a B.S. in Industrial Management from National Formosa University in 2012 and an M.F.A. in Fine Arts from Taipei National University of the Arts in 2018. This background across two very different fields has shaped his focus on the tension between order and loss of control, and on how personal experiences reflect larger social structures.

From the Production Line to Painting

Cai Ruei-Heng’s journey as an artist did not begin with a conventional fine arts education. After majoring in Industrial Management, he worked for nearly a year in a factory. On the production line, where standardized processes governed every step, he was responsible for inspecting and controlling product quality. It was a job that demanded precision, where every error had to be eliminated.

He recalls his first impression of the factory floor: machines running without pause, workers moving in sync as part of an endless chain, every action measured and regulated. In that silent, repetitive routine, he became aware of the pressure and absurdity that hid behind a seemingly solid order. This experience later became central to his artistic practice. The factory operated under a simple logic: unqualified products had to be discarded. Yet Cai often felt conflicted when confronting these so-called “defects.” Many did not look bad at all; some were even appealing, yet they failed to meet the set standards. Day after day, this contradiction grew stronger. “The factory’s standardization reminded me of the rigid systems of society,” he explains. “Everyone is on this production line that cannot stop. The question is, how do we face it? I realized that the way we respond is what interests me most.”

It is like standing on a conveyor belt that never stops, until one day, unexpectedly, you decide to jump off. Even years later, these factory memories continue to shape his work. Whenever he sees an assembly line or any other regulated, mechanical process, he experiences the same impact. For Cai, that experience remains a metaphor for the social structures we inhabit. It has become embedded in his artistic language, giving his work a distinctive balance: rational, analytical clarity paired with instinctive sensitivity. His paintings can dissect and categorize, yet they also embrace ambiguity and uncertainty.

Painting Intuition and a Collage Logic

“This is not a choice; it is a necessity. I must do this because it is who I am.” This is how Cai Ruei-Heng describes his relationship with art. After entering Taipei National University of the Arts for graduate study, he quickly found his direction and understood the scope of what he could achieve. His training in industrial management was not abandoned; instead, it became a framework for his thinking in practice. He recalls how his experience with AutoCAD sharpened his sensitivity to planar structures. Yet on canvas, he deliberately lets the lines slip into blurs and tangles. They are no longer precise design plans but resemble toys dismantled and reassembled.

His partner adds, “Many people think his work is all about inspiration, but behind it lies a strong, process-based logic. This comes from his technical background, and he’s good at breaking steps down and then putting them back together.” Cai’s compositions rearrange fragments of daily life and assorted elements, allowing new relationships to emerge through dismantling and recombining. Before painting, he produces a large number of sketches on paper, keeping them like stored materials ready to be pulled out, spliced, and reshaped into images with a self-reflective quality.

Cai admits with a smile that his works rarely have a clear endpoint. “I often work on many pieces at once. Some remain unfinished for a long time until I feel they need something, and then I add to them.” This “delayed completion” keeps his work open, never closed in conclusion, but always shifting, piecing, and regenerating. He also acknowledges that when creation becomes a dialogue between the body and the image, his brushstrokes often hesitate or tremble rather than flow smoothly. He has always felt uneasy with “intuition,” and this discomfort turns into hesitation and vibration on the canvas. Lines and colors become more than mere depiction; they carry the traces of emotion and bodily response. His paintings thus hold an energy that is uncertain yet genuine, like the lingering breath of a body caught in hesitation.

The Metaphor of Dampness: Island, Body, and Unease

For Cai, “dampness” is not only a familiar aspect of Taiwan’s climate but also a texture that permeates the body and emotions. Growing up on a hot and humid island, he became accustomed to the musty smell after sudden afternoon rains and the lingering moisture in the air. Over time, he has transformed this dampness into a visual language, absorbed into color and surface.

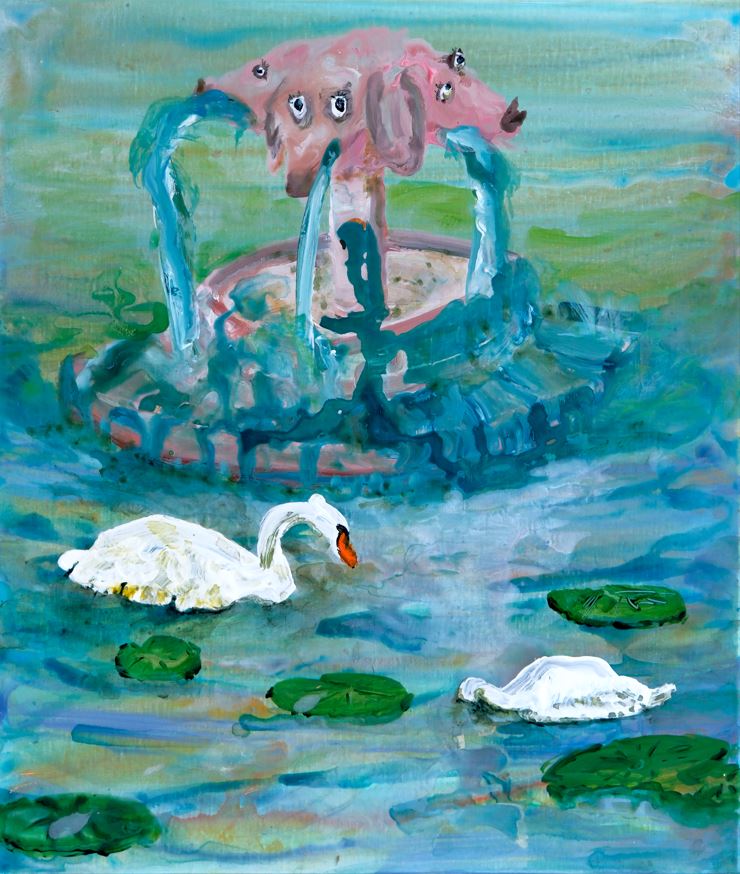

His paintings often convey a sense of absurdity and disorder, reflecting the chaos of reality and thereby extending into the exploration of “hollow postures” of humans and animals. In these scenes, creatures appear without clear purpose, caught in damp, moldy, and chaotic spaces, drifting along with their surroundings.

This dampness is both a physical and emotional memory. For instance, Cai once spoke of a “moldy pink” in his work, inspired by the golden apple snails he encountered as a child in the countryside. That pink, mingled with the scent of damp mold and rain-soaked weeds, left a deep imprint on his senses and later re-emerged in his paintings.

“Dampness, for me, is not only the memory of the body and of the island. It is also a reflection of unease,” he says. Dampness thus becomes a metaphor, pointing both to the island’s climate and to feelings of repression and uncertainty in personal and social life. Within such an environment, how should living beings position themselves? This is the question Cai poses to the viewer.

Between Presence and Absence

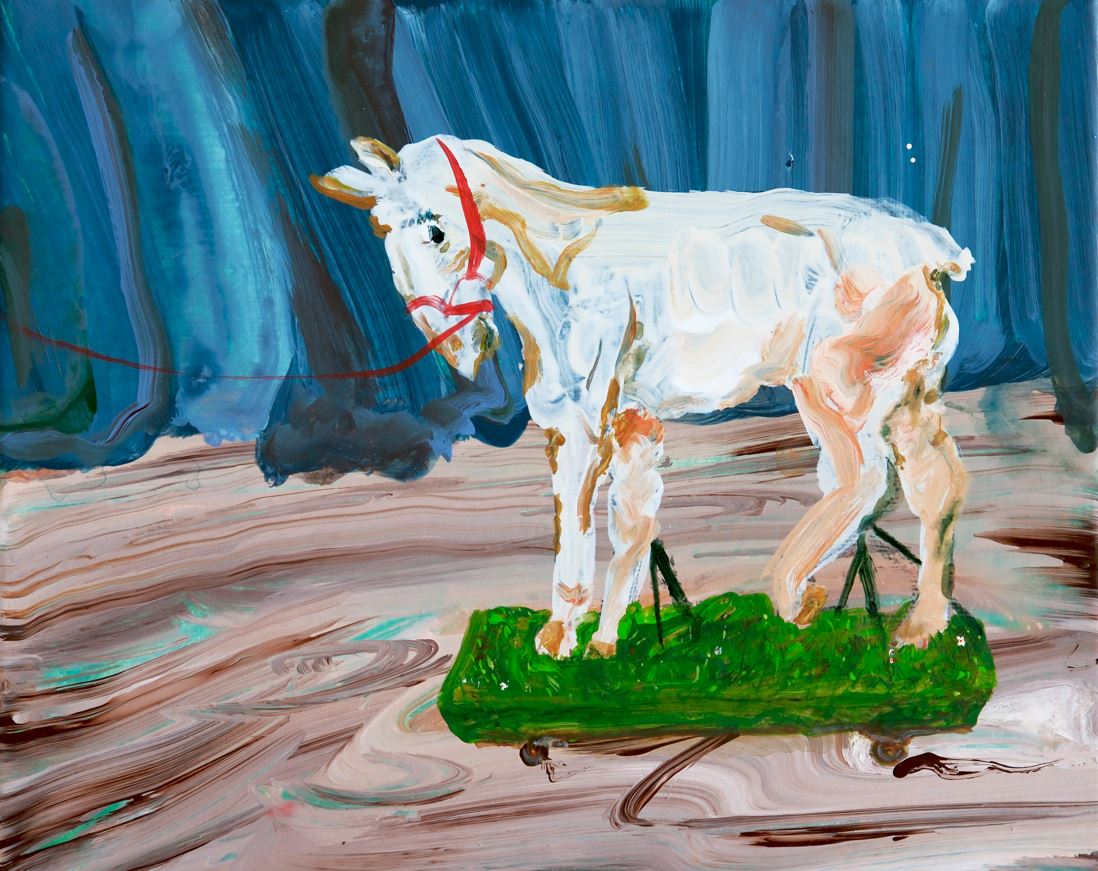

The figures in Cai Ruei-Heng’s paintings often hover between human and animal, dog-like, donkey-like, or ghostly forms that appear incomplete. They are at once familiar and strange, spectral presences that are clearly there yet seem out of place in the time and space they inhabit.

In the exhibition’s key work, Desolate Smoke and Wetlands, a blue donkey slowly opens its eyes and walks quietly across the canvas. Around it gather images that are neither horse nor donkey, neither human nor dog. They echo one another but never connect, caught in a fractured coexistence. These ghost-like forms create both restlessness and a sense of romance. Cai positions this condition as the central narrative of the exhibition, a kind of “purposefulness” that seems to exist yet cannot prove its belonging. To heighten this ambiguity, he deliberately thins the layers of paint, keeping figures and backgrounds apart to preserve a sense of distance.

These shifting bodies not only point to blurred identities but also mirror the viewer’s own unease about existence. They are like hyenas pacing endlessly in a zoo enclosure, seemingly placed in a defined setting yet never at ease. This “pretend belonging” reveals the paradox of human life: the desire for recognition paired with the impossibility of complete integration.

Absurd Gestures and “Soft Resistance”

When speaking of the “absurd,” Cai offers a vivid image: people sliding down a water chute, their awkward postures confronting the undeniable pull of gravity. “It’s funny, and also a little sad,” he says. For him, absurdity is neither escape nor direct opposition but a stance, a way of responding to reality.

He once described his state of mind as “restless, but not daring to truly disturb anything,” a sentiment he also sees reflected in his generation. “Taiwan’s political situation has definitely shaped us. Unlike the previous generation, who fought with passion and intensity, we tend to move restlessly just beneath the surface.”

He describes this emotional tension as “furious and wanting to resist the world, yet not even daring to throw a plastic bottle into the sea, still hesitating over whether to toss a biodegradable bag instead.” This fragile balance between “soft resistance” and “surface obedience” has become a hidden energy in his paintings.

This exhibition feels like stepping into a damp room, where the air is slow and sticky, compelling us to confront the unease of existence itself. Cai does not offer clear answers. Instead, his figures, colors, and textures remind us that absurdity and tenderness often coexist. The wavering forms in his canvases resemble moss growing in corners after rain, thriving stubbornly amid uncertainty. Perhaps all of us, in our own dampness, are quietly molding and, in doing so, leaving behind our own traces.